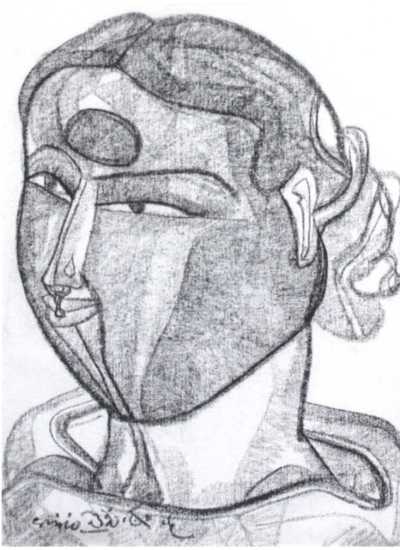

G R Iranna is an artist of reinvention who transforms his art and medium with the exigencies of the political turmoil that engulfs him. Like all artists who aspire beyond the mediocre, his works capture the zeitgeist of the times he lives in and yet transcends the boundaries of time and space. Born in 1970 in the Sindgi, District of Bijapur, Karnataka, he currently lives and works in New Delhi. Brought up in the environs of a humble ashram to a family of Shaivaite believers, GR Iranna retains a

Read More

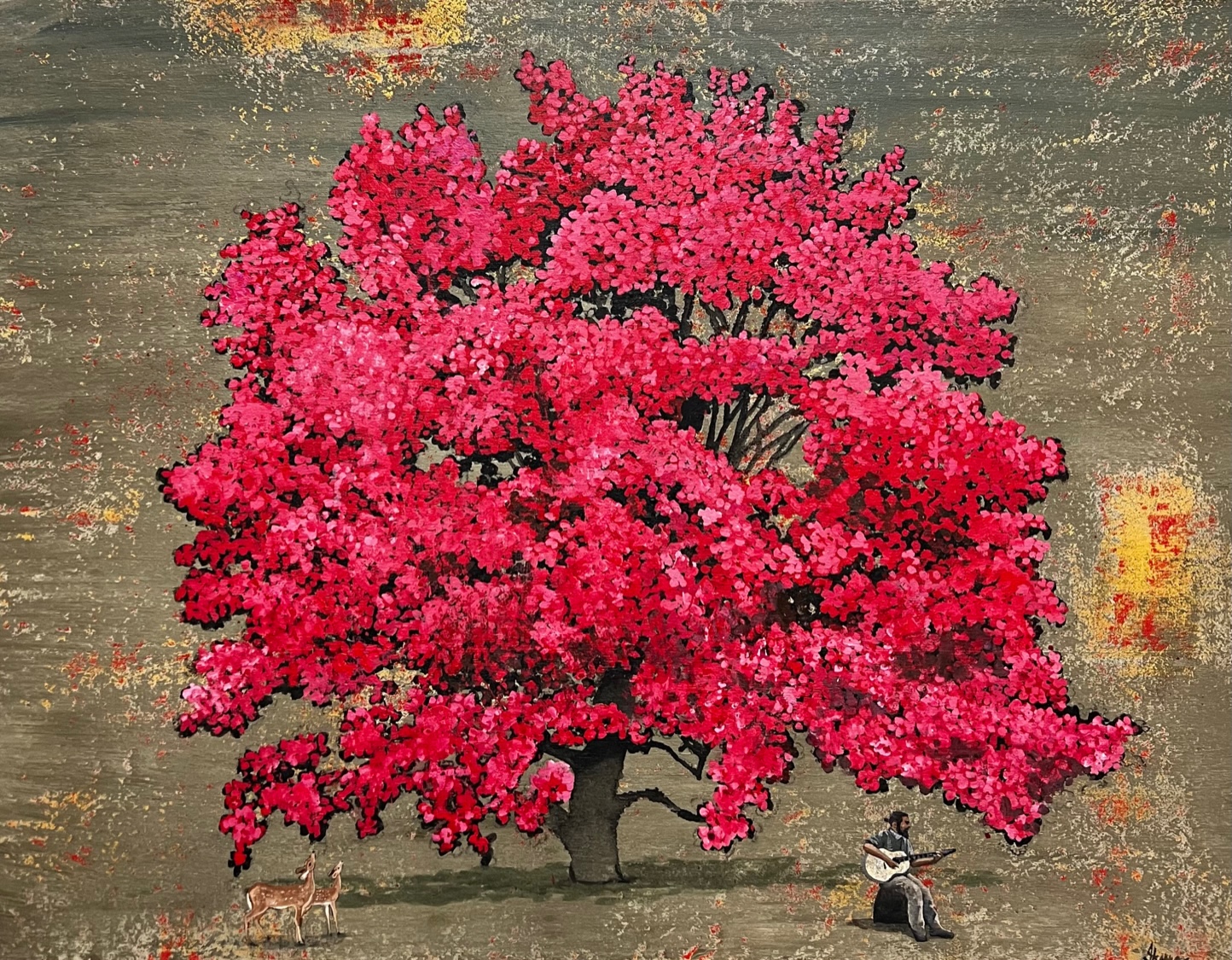

G R Iranna is an artist of reinvention who transforms his art and medium with the exigencies of the political turmoil that engulfs him. Like all artists who aspire beyond the mediocre, his works capture the zeitgeist of the times he lives in and yet transcends the boundaries of time and space. Born in 1970 in the Sindgi, District of Bijapur, Karnataka, he currently lives and works in New Delhi. Brought up in the environs of a humble ashram to a family of Shaivaite believers, GR Iranna retains a moral compass attainted at a young age in his art. This is evident in his acrylic works done on tarpaulin, titled “Ethereal Tree” and “Lofty Tree” where he engages with ash as a substance and essence in his works. In Shaivaite traditions, a new born child is anointed with ash to mark how central, mortality is to our existence. His use of the medium is also in essence homage to this thought. His paintings are known to be removed from a postmodern logic and engage in the usage of representative modernist language of Indian contemporary art.

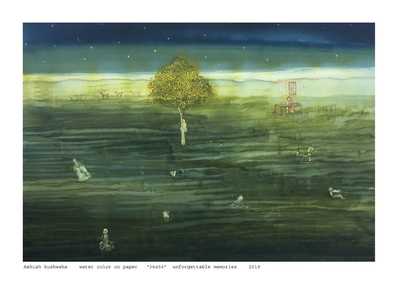

In Iranna’s earlier works, one can trace the development of certain central motifs in resonance with modernism in Indian art. He deploys adeptly the metaphors of tree, globe and carpet to depict the aspects of human condition and survival. For example the tree has been integral to his work because it embodies life in its silence, its stillness and meditative quality. The cut tree, with its veins and its sprawled branches recurs in his work. Very presciently he explains that the stump of the cut tree is still connected to the larger humanity through the elements, and this is an inference to how even when one transforms into an anti social element, like a terrorist, he/she continues to be a part of the society they were born into.

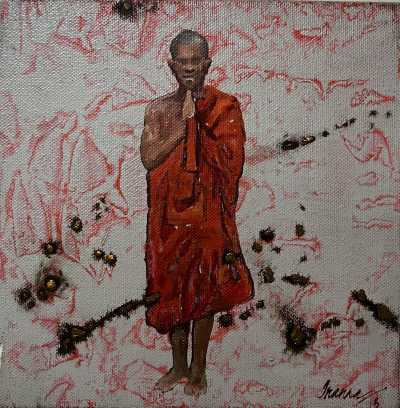

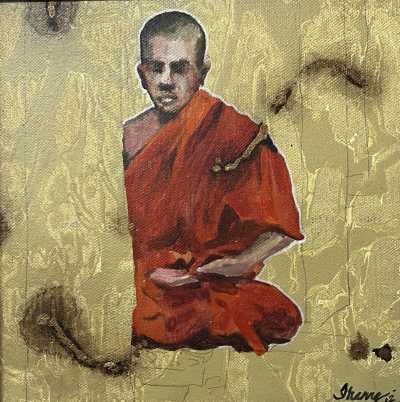

Similarly the metaphor of carpet is indicative of religion as it is used in many faiths to pray upon, to approach God and to place before divinity one’s vulnerability, hopes and dreams. His carpet also depicts erasures, both habitual and violent. In the more violent erasure, the carpet is punctured with bullet holes and wounds which refer to religious intolerance and the violence that is born of it. His series on Monks also engages with theme of religion and where the Bhikshu monks painted on tarpaulin inhabit in-between spaces standing, crouching or sitting in groups against blank or abstract backgrounds. For Iranna the figure of the monk points towards peace, an absence of desire, struggle and longing manifesting as transcendence in the search of meaning, marked in the absence of faces, or facial expressions and depiction of journey without a destination. He uses the “Buddhist iconography as a metonym for larger questions, in his search to understand the Being against the backdrop of our incomplete mortal journeys. His interventions show our failure at explaining our origins while personalising them as an artist opens up questions of universal and particular”.

The central metaphors in Iranna’s art have also seen metamorphosis, moving from concrete figurations to abstraction where he draws more on patterns and erasure of patterns. But through it all, the human condition remains the core of his creations. From his concern over liberalization of the economy in a nation striving to modernize itself and the impact this had on art, the police state emerges as a theme in his latter works. His art also was malleable to change over the years, depicting pain as an abstract force and the torment of resistance which were visualized in bruised textures in his art.

Through this gradual organic movement towards abstraction where metaphors became more subtle, Iranna moved on to the third dimension and started working on sculptures. This move came from a yearning to express himself in a more physical medium, involving in touching and moulding the form as well as in creating actual interventions in space. While his earliest sculptural innovations were an extension of metaphors from his paintings, which can be seen in his work using fibreglass titled “The Silencer”, he later on consciously developed a different language for his sculptures and installations, independent of his paintings. This emerged very aesthetically in his installation of a donkey in fiberglass in his series titled ‘Wounded Tools’, where he had hired a live malnourished donkey to study the sinews of its muscles and movement to recreate it. The art installation depicts the donkey going up in the air while still being harnessed to a cart carrying wounded tools, depicting the continuing servitude to the master. His installations and sculptures alert us to the pervasiveness of violence and how all of us are permeable to violence in our lives, even if in different degrees. The best epithet given to GR Iranna is perhaps the one coined for him by Ranjit Hoskote, ‘The Dancer on the Horse’. This epithet reflects how Iranna “balances his inner spirituality with the technical demands of the artistic medium, producing work which is both moving and aesthetically pleasing as well as shows an artist's obligation to find the right relationship between the private space of the studio and the public space of the gallery”.